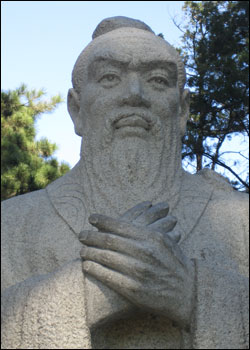

Vietnam's rich origins are evident throughout the Vietnamese culture. Spiritual life in Vietnam is a wide ranging array of belief systems, including Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Tam Giao (literally 'triple religion', which is a blend of Taoism, popular Chinese beliefs, and ancient Vietnamese animism).

Tet, one of the most important festivals in Vietnam lasts from January to early February. It heralds the new lunar year and the advent of spring and the celebration consists of not only raucous festivity (fireworks, drums, gongs) but also, quiet meditation. In addition to Tet, there are about twenty other traditional and religious festivals each year!

Vietnamese architecture expresses a graceful aesthetic of natural balance and harmony that is evident in any of the country's vast numbers of historic temples and monasteries. The pre-eminent architectural form is the pagoda, a tower comprised of a series of stepped pyramidal structures and frequently adorned with lavish carvings and painted ornamentation. Generally speaking, the pagoda form symbolizes the human desire to bridge the gap between the constraints of earthly existence and the perfection of heavenly forces. Pagodas are found in every province of Vietnam. One of the most treasured is the Thien Mu Pagoda in Hue, founded in 1601 and completed more than two hundred years later. In North Vietnam, the pagodas that serve as the shrines and temples of the Son La Mountains are especially worth visiting. In South Vietnam, the Giac Lam Pagoda of Ho Chi Minh City is considered to be the city's oldest and is notable as well for its many richly-carved jack wood statues.

As a language, Vietnamese is exceptionally flexible and lyrical, and poetry plays a strong role in both literature and the performing arts. Folk art, which flourished before French colonization, has experienced resurgence in beautiful woodcuts, village painting, and block printing. Vietnamese

lacquer art, another traditional medium, is commonly held to be the most original and sophisticated in the world. Music, dance, and puppetry, including the uniquely Vietnamese water puppetry, are also mainstays of the country's culture.

Although rice is the foundation of the Vietnamese diet, the country's cuisine is anything but bland. Deeply influenced by the national cuisines of France, China, and Thailand, Vietnamese cooking is highly innovative and makes extensive use of fresh herbs, including lemon grass, basil, coriander, parsley, laksa leaf, lime, and chilli. Soup is served at almost every meal, and snacks include spring rolls and rice pancakes. The national condiment is nuoc mam, a piquant fermented fish sauce served with every meal.

In the next few posts, I would be covering certain specific aspects of the Vietnamese culture and tradition. They include wedding, clothing, water puppets as well as religions and beliefs. I personally feel that they are the more significant identifications of Vietnam. This makes Vietnam’s culture and tradition different from any other.